TextX, Part 3: Curses Wrangling

In my previous post, we decided upon some general design choices. It’s time to present my first steps and show you all a mockup of TextX. I spent most of my time messing with Curses, as you may have guessed. So if you want to know a thing or two about the TUI library, here you go. Curses ahead!

curses.hpp

Curses is a C library, so the first thing I set out to do is to make curses a bit more palatable for C++’s sensibilities. Pretty much every function in curses revolves around one data structure called a “window” (no relation to the operating system concept). A window represents a portion of your terminal screen, and most of curses’s methods involve these windows. It’s almost like you could represent a window as a C++ object. So that’s what I did.

And so WINDOW* became Window. It’s generally just the process of finding all the functions that work on windows and turning them into methods. But don’t worry, there was still plenty of pitfalls:

Initilization

Generally, when you invoke curses, you want to make a TUI application. To start curses, you invoke initscr, but that’s not nearly the end of it if you want something TUI-like. Here, let me show you:

initscr(); // start Curses

raw(); // disable ^C killing our application

noecho(); // don't echo characters (like, say, arrow keys)

keypad(stdscr, TRUE); // enable said arrow keys

scrollok(stdscr, TRUE); // enable scrolling

if(has_colors() == TRUE) { // if this terminal supports colors...

start_color(); // enable colors

use_default_colors(); // use the terminal's default colors instead of black/white

}

mousemask(ALL_MOUSE_EVENTS, NULL); // accept mouse events

clear(); // clear the screen

refresh(); // ACTUALLY clear the screen

// Okay, now we can actually startThere are probably functions I don’t know about yet that need to go here, even. So be careful!

Subwindows

You get one big window at the start, stdscr, but I wanted to divide the screen into multiple windows. I came across a function that looked very helpful for this purpose, derwin, short for “derived window” (gotta love C’s love affair with cryptic shortened names). It allows your subwindows to share memory with the larger one, which is good because who wants double the space requirement? It allows them to automatically layer properly, avoiding the need to order your wrefreshes, which is also good because ordering is hard. So what’s not so good about them? I’ll let the man page do the talking:

BUGS

The subwindow functions (subwin, derwin, mvderwin, wsyncup, wsyncdown, wcursyncup, syncok) are flaky, incompletely implemented, and not well tested.And they’re right about that, too. I tried using them, and they’d render improperly… Most of the time. So no subwindows; just newwin for us. That’s okay, though, because windows made with newwin can still overlap, it just matters in which order you call wrefresh on them now. But… Allow me to highlight two lines in our startup code that caused me no end of grief:

keypad(stdscr, TRUE);

scrollok(stdscr, TRUE);Note that keypad is taking a window as an argument. That’s because arrow keys, function keys, etc. are enabled, for some reason, on a per window basis. Yes, wgetch, the function to get a key from the keyboard, takes a window as well. wgetch even refreshes the window you call it on… Again, for some reason. So when I had subwindows do all the drawing, but stdscr taking in input, the whole screen would clear when I pressed a key. I didn’t want to refresh stdscr! When I figured that out and moved the call to wgetch to a subwindow, suddenly arrow keys stopped working. Why? Because keypad is per-window!

scrollok is a problem too, because…

Scrolling

When I realized how keypad worked, I made sure every new window was born with keypad and scrollok enabled. But as it turns out, you really shouldn’t allow 1-line-long windows to scroll. I spent a while wondering exactly why said windows never had anything I put in there actually in there. It was because the window was scrolling after it finished its 1 line of text! So be careful where you use scrollok.

textx.hpp

Now, onto how TextX will actually be structured. First off, the UI’s design has to be considered:

- There will be

Apps. An app is something like a text editor or a dialog. It gets a portion of the window it can draw into, and it receives keystrokes while in focus. - There will be

Panes. A pane contains apps or other panes. Panes implement things like split views, tabs, etc. - There will be a status bar that apps can write into at the bottom of the screen.

- There will be a menu bar that apps will provide options for at the top of the screen.

Pretty simple, right? Yeah, actually. The hardest part is simply figuring out what the API between Apps and Panes should be. Eventually, I decided on this: Panes contains 0 or more Apps and 0 or more child Panes. Panes provide the status bar to Apps, usually a part of thier own window. Apps have titles, which Panes can display if they want to (like, for example, in a tab pane). Apps provide menu options, which the root Pane renders (not and child panes). The App with user focus controls the status bar and the menu bar.

It’s all boring software engineering. So onwards to a more complex system…

colors.hpp

TextX should be in color! But color in curses is hard sometimes. You have a finite number of color pair indices, which you can assign to from a finite number of color indices, which you can give an RGB color value. Every single character on the screen then has a color pair index associated with it. Changing the color indices of a color pair index will change colors on the screen immediately.

This raises some problems. What if there are two apps, each of which wants to show some different colors? If both apps set the same color index to different values, only one of them will take effect; both sections will show up as the same color instead of 2 different ones. So we need a mechanism to ensure everyone who wants a custom color can get it.

I chose a system in which you request ColorPair objects, which are reference counted and stored in a cache. We can use this cache to select a new index when someone requests a new color, and also to serve an existing color if one is being used. Color indices can then get added back to the pool of available ones when they’re no longer used. When you hit the limit of color pairs used at once (16 on most platforms)… It crashes. In the future, it will probably just serve you the default color pair. But for now? No rainbow text, sorry.

We can’t just use destructors and RAII magic to reference count these colors, though. A color may go out of scope, but it can still be on the screen somewhere! So, sadly, you must manually call a dispose method on the colors. But other than that, the system works: You request colors, you get colors, you draw in color!

Results

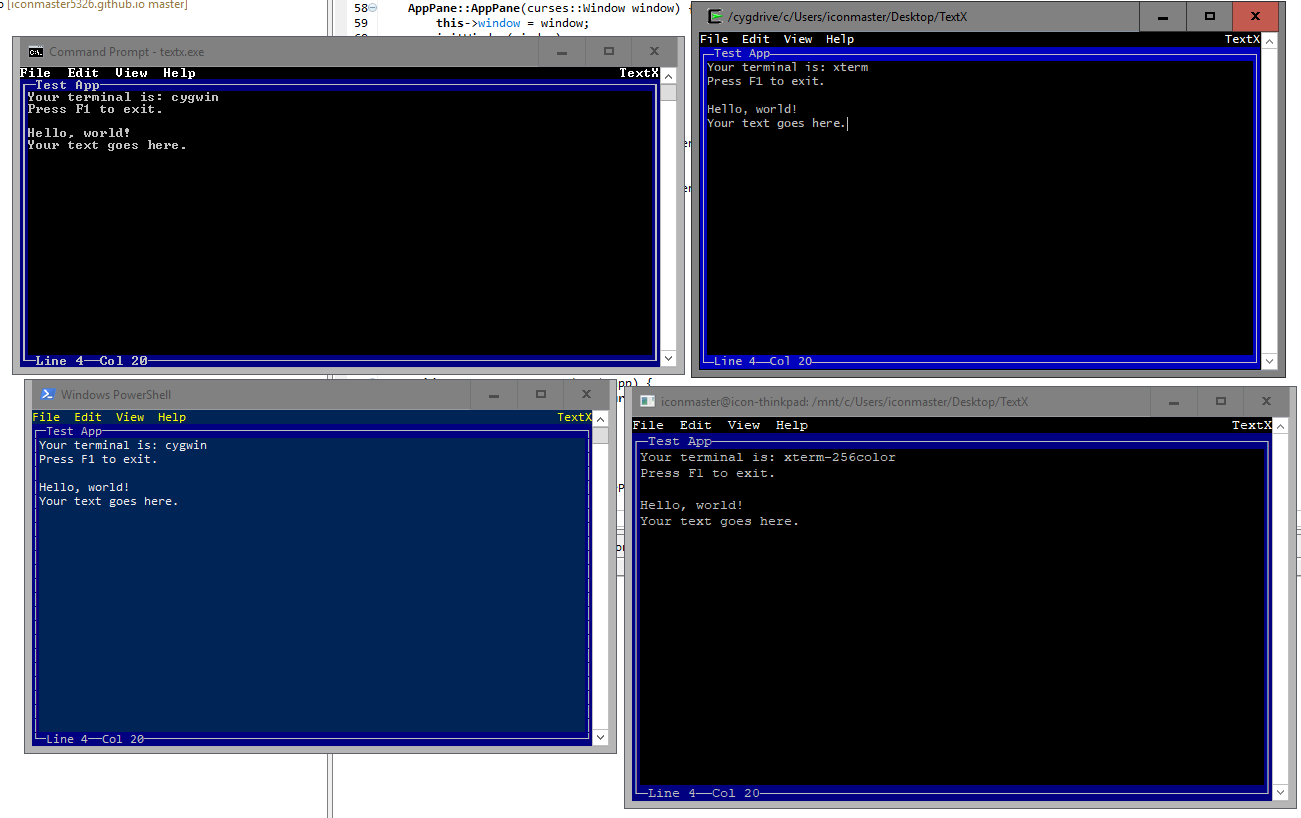

So, with colors, apps, and panes working, here’s what TextX might just look like:

From the top left, clockwise: Windows, Cygwin, Linux, PowerShell

From the top left, clockwise: Windows, Cygwin, Linux, PowerShell

You can input text, even. It doesn’t save it anywhere, but by golly, you can hit letter keys and those letter keys appear on screen. I consider it a success so far!

So onwards, then. Next time, I hope to implement some actual text editing. In the mean time, be sure to check out TextX’s repository, perhaps to help me see how it looks on other terminals. If you try it out, screenshots, please!