TextX, Part 2: C And Curses

In my previous post, I drafted some important design considerations for TextX that precede the writing of any code. There are two of them:

- What language should TextX be developed in?

- Is it possible for us to use curses while being portable and single-executable?

I’ve done some research, and here are my findings.

Question 1: C or C++

For maximal portability, you really only have one choice, and it’s C. Luckily, the most common C compilers (gcc and clang) come with C++ support right with the C compiler, but C++ is still slightly less widespread than C itself. It’s also important to figure out what standard of C/C++ we want to target; having the features of a newer standard would be real nice!

We need a way to figure out what the lowest-common-denominator language version most machines are on. I compiled this table, with some helpful dates to figure out what we want to do:

| Standard | Compiler | Release year | Year made default in Ubuntu |

|---|---|---|---|

| C89 | ??? | after 1996? | before 2010? |

| C99 (1) | gcc 3.3 | 2003 | before 2010? |

| C11 | gcc 4.9 | 2015 | 2016 |

| C++98 | ??? | after 2003? | before 2010? |

| C++11 | gcc 4.8.1 | 2013 | 2014 |

| C++14 | gcc 5.1 | 2015 | 2016 |

(1): Full support was claimed in 3.3, but bugfixes for C99 features came as late as GCC 4.5.0, released in 2010.

As you can see, C89 and C++98 are such ancient history at this point that I can’t even determine what gcc versions first support them. Slightly worrying that this human knowledge has seemingly been lost, but I’m sure I just didn’t comb through the changelogs hard enough. It should also be noted that Ubuntu does not keep track of what packages it had available before 2010 (with its Hardy release). Also slightly worrying.

Anyways, this provides a good chart of how far back we have to go to support older machines. If we only want to support machines 4 years old or newer, C++11 is safe to use… Which means we can’t use C++11. That’s a shame, because C++11 is a pretty important C++ standard; it adds a lot. C99, however, is almost certainly widely adopted even in machines a decade old. This makes me want to use C to write TextX, although being stuck with C++98 isn’t 100% a deal breaker.

But what about non-Linux platforms? What strange and fun platforms do we want to support?

- Windows: MSVC 2017 doesn’t have full support for C99. Yes, that’s right, the most recent version of MSVC does not support a C standard released over 20 years ago. C99 support is only partial, so using it would involve much trail and error. MSVC 2017 only just added C++11 support as well. I’m surprised it has C++98 support, actually… Anyways, MinGW looks like the best bet here. Windows has this nice feature where you can compile it once and it’ll work on pretty much every Windows machine in existence.

- Mac: I have no clue how Macs work, I have to admit. I assume they work like Windows in that Mac binaries work on all Mac machines, but I have a feeling I’m wrong.

- The BSDs: They all seem to use some variety of gcc historically; FreeBSD and OpenBSD now use clang, though. So see the above table.

- Solaris: The Sun C compiler came out with C++11 in 2014. The oldest thing I can find claiming C99 support is from 2010, which gives me hope that 10ish year old versions support C++98 and C99. But Oracle has done such a bad job preserving its version history that I really have no clue about older versions.

- DOS: This might sound silly, but I’m sure there still exist DOS machines in production! MSVC 1.5 came out in 1993, and Borland Turbo C++ 5.0 came out in 1997. So it’s not even C++98 or C99. We have no hope of developing portable C/C++ code on this platform.

- OS/2: Okay, now we’re definitely getting silly.

So… C99 or C++98. Pretty much every C compiler from around a decade ago is also a C++ compiler, so it’s purely a matter of preference between the two. Which one will I choose?

Arguments for C:

- Ever slightly more portable. One day, we may want to port it to a system with a C but no C++ compiler.

- C++, especially C++98, has a lot of boilerplate I’d rather not deal with.

Arguments for C++:

- Objects can be pretty convenient.

- The STL is even more convenient.

- C makes you reinvent a lot of wheels, mainly because no STL.

So it seems C++ is the way to go here. C++ it is. C++98, though, due to the compatibility concerns as outlined above. Time to party like it’s 1999!

Question 2: Curses or Not

(And by curses, I mean ncurses. There exist other curses implementations, such as pdcurses, but those don’t work very well at all.)

Last time, I identified two big fears with using curses:

- The Windows build will need to be shipped with terminfo files so it knows how to work terminals.

- It will be difficult to compile curses statically into our application.

ncurses, much to my relief, circumvents all my fears. When built with MinGW, it uses the Win32 console API when $TERM isn’t set, circumventing the need to ship it with terminfo on Windows. And it can be very easily linked in statically! With Linux, it turns out to be pretty darn easy. Once you’ve used your favourite package manager to get ncurses and gpm, compiling like this is sufficient:

gcc -static ... -lncurses -ltinfo -lgpmMinGW and ncurses is even simpler. Just get x86_64-w64-mingw32-ncurses as well as x86_64-w64-mingw32-gcc, and…

x86_64-w64-mingw32-gcc -static ... -lncursesCygwin will follow the same steps, just with your regular old gcc. And then there you go! ncurses on two platforms!

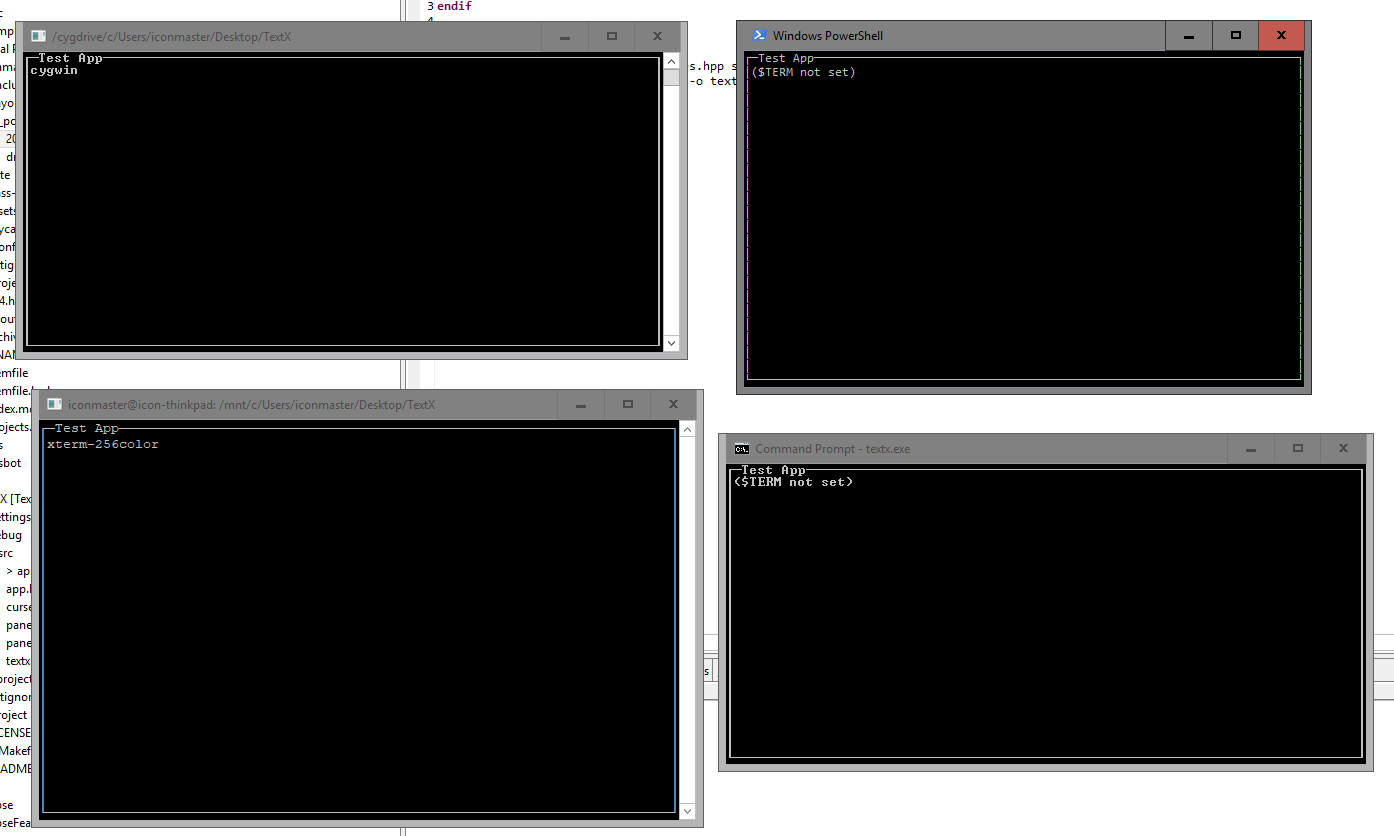

From the top left, clockwise: Cygwin terminal running Cygwin build, PowerShell terminal running MinGW build, Windows terminal running MinGW build, WSL terminal running Linux build

From the top left, clockwise: Cygwin terminal running Cygwin build, PowerShell terminal running MinGW build, Windows terminal running MinGW build, WSL terminal running Linux build

The only problem I’ve found with ncurses so far is a bug: If you compile ncurses with MinGW, and then call a ncurses application with $TERM set, it crashes. That’s a pretty big bug, but at least it could possibly be fixed? So, in the end, looks like we’re using ncurses. I was kind of hoping to make a new TUI library, but in the end it’s probably better that I don’t reinvent the wheel, despite this wheel’s many problems and quirks.

What Next?

Implementation, of course! Next time, I hope to begin showing you the design TextX will have in C++, as well as some first steps towards realizing that design. In the mean time, be sure to check out TextX’s repository as it evolves. If you’re interested, please give me your feedback!